By Nick Opara-Ndudu

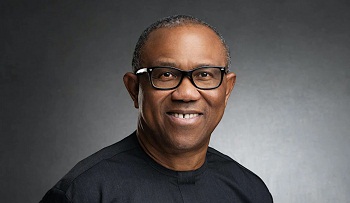

In recent times, it has been generally acknowledged that no personality has stirred the nation’s political space as much as Mr. Peter Obi, the presidential candidate of the Labour Party since he took the bold step of contesting Nigeria’s presidency.

As the phenomenon continues to unfold, those who gave Peter Obi very minimal attention are coming to terms with the realization that it is not a fluke after all. Once described as “a group of four young persons in a room” whose only tool was the internet, an organic movement of young people and other concerned Nigerians, self-motivated and selfless in their pursuit of a better Nigeria, have since ensured that the phenomenon takes on a life of its own.

Initially derided as lacking in “structure”, the energetic young people who dominate this movement, have ensured that in a determined competition for influence that their relevance and electoral value are recognized and acknowledged in determining the outcome of the 2023 elections.

In Peter Obi, they appear to have found a candidate capable of shouldering the weight of their collective aspirations for a better and more prosperous nation. And the essential drivers of their campaign have been Peter Obi’s character, competence, and capacity when compared with other candidates and their belief in his ability to provide transformative leadership for the birthing of a new Nigeria.

With the “consumption-to-production” mantra, which is intended to underscore the need to evolve a truly productive nation, Peter Obi has craftily and ingeniously defined the thematic and philosophical foundation of the leadership and governance template he intends to pursue if availed the opportunity of superintending over the affairs of our beleaguered nation.

Metaphorically speaking, the pursuit of this would be a challenge to the existing order characterised by what could be referred to as Nigeria’s paradox of productivity. This lamentable paradox has found expression in the failure of the system to fairly reward the contributions by the component units of the federation to our commonwealth in a manner that values and recognises the burden of production and rewards productivity.

Another perspective to this paradox is our failure to energise the economy through the pursuit of production-oriented governance whose objective would be to encourage different parts of the country to focus on agro-industrial policies that seek to realize the potentials in their areas of comparative advantage.

With a population of over 200 million people, such a production-centred economy would benefit from a huge local market for the goods and services that would be the outcome of an aggressive value-addition program for local commodities.

In substantive terms, the existing order has failed to reward productivity in a fair and equitable manner whilst also discouraging industrial production in preference for a rentier economy largely defined by a destructive patronage system. Regrettably, this has remained an albatross to Nigeria’s development and progress.

By reiterating and drawing attention to the innate potentials of the vast lands in northern Nigeria, Peter Obi has rekindled hope in the fact that the North actually holds a vital key to Nigeria’s future prosperity. Indeed, what has held us back is the rudderless and inept leadership that has been foisted on us over the past decades and which has blurred our vision of the North and, in fact, all parts of Nigeria as fiscally sustainable entities in a truly federal system.

Unleashing the latent potentials of the vast acreages of land across Nigeria through a marshal plan that focuses on Agro-industrialisation would be critical in tackling this paradox of productivity that has held back Nigeria in the backwaters of development.

In doing so, the Niger Delta, for instance, would have access to, and significant control over its mineral resources in the same way that the vastly developed and cultivated arable land of the North would create greater access to wealth and opportunities for our brethren in the North.

As a matter of fact, it needs to be acknowledged that the vast Agro potentials of the North, and indeed the whole of Nigeria, if properly harnessed would make revenues from fossil fuels pale into insignificance. The contribution of agriculture to the economy of countries such as The Netherlands, Israel, Ukraine, etc. underscore what the agricultural sector is capable of doing for Nigeria under the right leadership.

The challenge is to evolve an elaborate value-addition program that would focus on providing enhanced and more rewarding opportunities for the rural farmers driven by extensive opportunities for local processing of Agro commodities. The multiplier effect of such a program in terms of enhancing food security and creating jobs would be a veritable game changer in our race against poverty and reducing criminality.

As simplistic as the “consumption-to- production” mantra would appear, it seeks to reorder our priorities by encouraging the pursuit of the potentials that abound in different parts of Nigeria. The overriding need is for different parts of the country to focus on the commodities in which each region has a comparative advantage.

In the final analysis, each region would be the anchor and driver of an industrialization program that aims to satisfy the needs of Nigeria’s 200 million plus population. And beyond that, the potential of exporting various goods and services are better imagined particularly with the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (A.C.F.T.A).

From consumption to production and the “Dangotisation” of Nigeria’s productive capacity

If anyone is in doubt as to what is possible in this regard, an in-depth study of the transformation of Nigeria’s cement industry is recommended if an understanding of the full ramifications of the impact of Peter Obi’s agenda as espoused via the “consumptionto-production” mantra is desired.

Without doubt, Nigeria requires a bold industrialisation initiative to transform from a nation noted for its excessive reliance on importation to meet domestic needs to a production-based economy.

The initiative could be encapsulated in a marshal plan that seeks to chart a path towards local production of finished goods for which there is an abundance of raw materials locally.

Import substitution strategy – the Dangote example

One would easily recall that Nigeria was a net importer of cement until the foray ofDangote Industries PLC and other indigenous firms into the local production of cement.Currently, cement producers include Dangote Industries, Lafarge Group, Bua Group,Ibeto Industries, etc.

Prior to this time, Dangote Industries PLC was a major importer of cement. During thisperiod, Nigeria’s annual cement import bill had peaked at US$237 million in 2007reducing to US$103.6 million (2012), US$3.4 million (2017) and US$2.6 million(2020). Through a carefully articulated backward integration strategy, the companyalong with other cement manufacturing companies were able to process locallyavailable raw materials into cement and progressively wean the country off dependenceon imported cement.

This initiative involved granting these companies access to a wide range of incentiveswhich enabled them take advantage of the huge local demand in building verysuccessful local brands. With a market of 200 million people, Dangote PLC and othercement producers have been the major anchor and drivers of an import substitutionstrategy that has saved the country foreign exchanges that would have been committedto importation of cement and in the process created millions of jobs for the localpopulation.

Through a similar initiative, Dangote PLC is today constructing, perhaps, the biggest crude oil refinery in the world. When completed, the refinery is expected to satisfy thelocal demand for petroleum products. Besides the huge savings in foreign exchange, therefinery would create millions of jobs for the local population.

Through a similar initiative, Dangote PLC is today constructing, perhaps, the biggestcrude oil refinery in the world. When completed, the refinery is expected to satisfy thelocal demand for petroleum products. Besides the huge savings in foreign exchange, therefinery would create millions of jobs for the local population.

The lessons of the Dangote experience

In the same way that Nigeria was able to substitute importation of cement with localproduction, it is possible to pursue an aggressive import substitution strategy focusedon at least one hundred (100) different products in which we have comparativeadvantage in terms of the availability of raw materials locally.

With similar or comparable incentives as were extended to Dangote PLC, Nigeria canpursue an aggressive import substitution strategy focused on value-addition to local rawmaterials over a ten-(10)-year period. This would lead to the creation of huge industrialconcerns with attendant benefits in the area of foreign exchange savings, creation of jobopportunities and real diversification of the local economy.

With a population of 200 million people, the impact of such a strategy would be hugelytransformative with the potential of turning Nigeria into Africa’s industrial powerhouse.Beyond Nigeria’s 200 million plus population, the emerging industrial enterpriseswould be uniquely positioned to take advantage of the opportunities in the AfricanContinental Free Trade Agreement (A.C.F.T.A.).

What Peter Obi seeks to provide is the leadership with the requisite political will to challenge this paradox of productivity that encourages consumption with very scant regards for the producers of our commonwealth while at the same time inhibiting the ability of virtually all parts of our country to harness the vast potentials beneath the earth for the benefit of her citizens and the evolution of a truly prosperous and united Nigeria.

NIGERIA NEWSPOINT